Vaccines, Lock-downs and Passports

Effect of Vaccines

Our colleagues on the continent seem to be looking to the vaccines as a way of curbing a rampant spread of the virus. It might be worth pointing out that in Great Britain there was no discernible beneficial effect of the vaccination programme on daily new cases; only on daily deaths, which they have enormously reduced. What is needed to curb in infection is stricter lock-down.

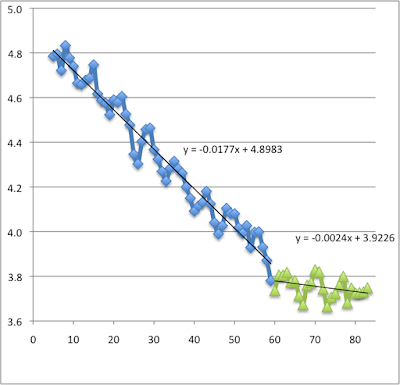

From 5th Jan 2021 till 28th Feb the semi-log plot of Log10 (daily cases) shows a monotonic decline with a halving time of 17 days. Since 1st March there seems to be a new slower rate of decline -- t(0.5) = 125 days. The epidemiological R number must be getting very close to 1.0. Perhaps this is the result of a return of children to schools, or perhaps a general relaxation of vigilance; an unexpected negative effect of vaccination. (See my previous posts to understand these calculations.)

Fig. 2 shows a semi-log plot of the logged death data averaged over the preceding 7 days, in order to smooth out the enormous dependence of number on day-of-the-week. There was a lag during January, while the lethal effects of December and Christmas took their toll. But from the beginning of February there has been an accelerating fall in daily mortality. The March data (pink squares) show a halving time of 11.2 days. And the decline is still quickening.

Lock-downs

Transmission can be controlled quite effectively in the absence of vaccine, but it takes discipline. If everyone took the precautions that the vulnerable and careful people have been taking for the last 12 months, the daily number of new cases should drop suddenly to zero in the space of 5 - 7 days. Britain has never got anywhere near that degree of discipline.

Vaccine-passports and Lock-down

There has been some talk of letting people into pubs if they show a card that confirms that they have been vaccinated. Many seem to favour the idea; many are opposed.

Once everybody in the country has been offered a vaccination, it does not seem necessary to request a passport. Those who wish to remain un-vaccinate will be taking a risk. But that is up to them. They should pose little threat to others who are vaccinated.

(See also: Variants of Concern

Covid Epidemiology part 5

Pandemic and new variants

SARS-CoV2 Continued

COVID-19 Epidemiology part 2)